Published on Nov 15, 2023

This story was originally published by ProPublica.

Forrest VanPatten was 50 and strong after years as a molten-iron pourer when he learned in July 2019 that a hyperaggressive form of lymphoma had invaded his body. Chemotherapy failed. Because he was not in remission, a stem cell transplant wasn’t an option. But his oncologist offered a lifeline: Don’t worry, there’s still CAR-T.

The cutting-edge therapy could weaponize VanPatten’s own cells to beat back his disease. It had extended the lives of hundreds of patients who otherwise had no chance. And VanPatten was a good candidate for treatment, with a fierce drive to stay alive for his wife of 25 years and their grown kids.

VanPatten didn’t know it, but he also had the law on his side. His home state of Michigan had long required health insurers to cover clinically proven cancer drugs.

He and his family gripped tight to the hope that the treatment promised.

Then, his insurance company refused to approve it.

Across the country, health insurers are flouting state laws like the one in Michigan, created to guarantee access to critical medical care, ProPublica found. Fed up with insurers saying no too often, state legislators thought they’d solved the problem by passing hundreds of laws spelling out exactly what had to be covered. But companies have continued to dodge bills for pricey treatments, even as industry profits have risen. ProPublica identified dozens of cases in which plans refused to pay for high-stakes treatments or procedures — from emergency surgeries to mammograms — even though laws require insurers to cover them.

Companies can get away with this because the thinly staffed state agencies that oversee many insurers typically don’t open investigations unless patients file complaints. Regulators acknowledge they catch only a fraction of violations. “We are missing things,” said Sebastian Arduengo, an assistant general counsel for Vermont’s insurance department.

In the 34 years since Michigan began to require cancer coverage, regulators there have never cited a company for violating the law.

Like most policyholders, VanPatten had no insight into the decision made by his insurer, a nonprofit called Priority Health that covers about a million Michigan residents.

He didn’t know that around the time the therapy won the Food and Drug Administration’s approval, executives at Priority Health had figured out a way to weasel out of paying for it.

Through interviews with former employees and a review of company emails and VanPatten’s medical records, ProPublica was able to crack through the usual secrecy and expose the health insurer’s calculations.

Former employees said the decision not to cover this treatment and a related one was driven almost entirely by their high price tags — up to $475,000. Side effects that could land a patient in the hospital can push the bill over $1 million. Priority Health number crunchers calculated to the penny the monthly cost per policyholder if the company shifted the expense to them: 17 cents. But executives didn’t raise premiums or absorb the extra cost. They decided to save that money.

Patients’ needs weren’t part of the equation, recalled Dr. John Fox, then Priority Health’s associate chief medical officer. “It was, ‘This is really expensive, how do we stop payment?’”

Over Fox’s objections, fellow executives came up with a semantic workaround: These cancer drugs aren’t technically drugs, they argued, they’re gene therapies. All Priority Health had to do was to exclude gene therapies from its policies, and it could say no every time.

Priority Health said in a written statement to ProPublica that it provides compassionate, high-quality, affordable coverage and spends 90 cents of every premium dollar on member care.

“We are committed to making medical innovations available to members as quickly as possible, regardless of cost, as soon as they have been proven to be safe and effective,” Mark Geary, a spokesperson, wrote. The company said it initially didn’t cover CAR T-cell therapy because there was a “lack of consensus” about the treatment’s effectiveness.

“Major life-threatening complications and side effects were common, with a high rate of relapse,” the statement said.

At the time of VanPatten’s denial there was, in fact, already substantial consensus about the medication. In December 2017, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, then an alliance of 27 leading U.S. cancer treatment centers, spelled out in its guidelines for B-cell lymphomas which patients should receive the therapy and when. VanPatten’s doctor said he met the criteria.

VanPatten’s family signed a privacy waiver giving Priority Health permission to discuss his case with ProPublica. Nevertheless, Priority Health did not respond to questions about his case or whether the company had violated Michigan’s mandate to cover cancer drugs when it refused to pay for his therapy.

VanPatten was disappointed but tried to remain optimistic after the first denial in January 2020. He and his wife, Betty, who worked in medical billing, knew it often took an appeal to coax the insurer to approve care.

In early February, Dr. Stephanie Williams, then the head of the blood and marrow transplant program for Spectrum Health, came to see VanPatten in his hospital room on Grand Rapids’ Medical Mile. It had been more than six months since his diagnosis.

He was sitting up in bed hooked up to an IV. His face, once framed by reddish eyebrows and a signature goatee, was hairless and drained of color. Betty pasted on a tight smile.

Priority Health had denied the treatment again, Williams told them, though she vowed to keep fighting.

When she left the room, VanPatten swung his legs over the side of the hospital bed. He had remained resilient and good-humored through his illness. But at that moment, he felt like Priority Health was treating him like an expense, not a person. It got to him, the idea that the insurer he dutifully paid each month knew this was his only chance and was holding it just out of reach.

He grabbed a tissue box from a tray and hurled it against the wall.

Fox, whom Willams described as the “conscience of the company,” had long been the point person for oncology in Priority Health’s medical department. In his earlier life as a practicing physician, he had trained at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a chronic disease epidemiologist. When he joined Priority Health in 2000, he admired the company’s focus on preventive care and the fact that his bosses encouraged him to build deep relationships with local hospitals and doctors.

CAR T-cell therapy was a breakthrough more than 20 years in the making, and Fox had tracked clinical trials and talked to oncologists about it. By genetically reengineering patients’ own white blood cells, then infusing them back into the body to fight cancer, the treatment helped most participants in clinical trials get into remission within three months.

He knew this would be a game changer for patients. He also knew the law. So when news of the FDA’s approval of the first CAR-T medication, Kymriah, hit his inbox in August 2017, he recalled, “I said, ‘You know, we’re required to cover this. This is a treatment for cancer.’”

But the culture at Priority Health had shifted over the previous year under new leadership to focus on cost savings, Fox and four other former employees said in interviews. The company brought in a new chief medical officer, Dr. James Forshee, in late 2016 from Molina Healthcare, an insurer known for wringing profits out of Medicaid managed care plans.

In conversations about the new treatment, several former Priority Health employees recall, Forshee pointed out that the law required covering cancer “drugs,” and he argued that the new treatment actually wasn’t a drug; it was a gene therapy. (Through a company spokesperson, Forshee declined to comment for this article.)

Fox thought this was ridiculous. He pressed company lawyers for an opinion. Priority Health’s filings with the state “indicate that we have to cover FDA approved cancer drugs,” Fox wrote to two members of the legal department in a September 2017 email.

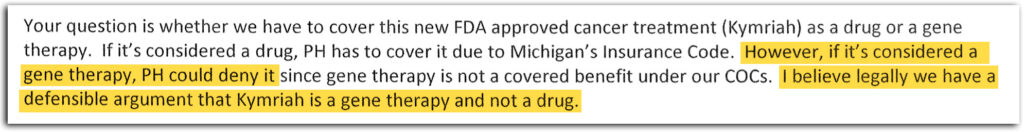

Senior counsel John Samalik responded, bolstering Forshee’s position that Priority Health didn’t have to cover Kymriah: “I believe legally we have a defensible argument that Kymriah is a gene therapy and not a drug.” (Samalik declined to comment through a company spokesperson.)

A September 2017 email written by John Samalik, a Priority Health senior counsel (Obtained by ProPublica. Highlighting by ProPublica.)

Fox pointed out that the company already covered another gene therapy. He told ProPublica that he suggested asking state regulators whether the cancer-drug mandate applied to Kymriah, but Forshee and at least one other executive refused.

“My inference being that, if we ask the state, they would say yes, so let’s not ask,” Fox said. Two other former Priority Health employees involved in the discussions confirmed Fox’s recollections.

The FDA approved a second CAR T-cell medication, Yescarta, seven weeks after the first approval.

When ProPublica asked if the FDA considered CAR T-cell therapies drugs, an agency spokesperson said yes. She wrote in an email that they have been regulated as gene therapies, and that they “are biological products and drugs under the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act) and the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act.”

Fox continued to push Priority Health to cover them; Forshee didn’t budge.

As they often did for new therapies, Priority Health’s actuaries calculated the price tag. They estimated that each year, one patient would need Yescarta and one Kymriah. If spread across the company’s members, the therapies would cost an extra 17 cents per member per month — 8 cents for Yescarta and 9 cents for Kymriah, emails show.

If the company had chosen to absorb the cost rather than raise premiums, the extra expense — potentially more than $1 million for each patient receiving the therapy — could have hurt its bottom line. Other insurers had also balked at the cost of CAR-T and were slow to cover it.

Priority Health made a slight tweak to its 2018 filings to state regulators, one with life-changing implications for patients like VanPatten. As it had in the past, the company said it covered drugs for cancer therapy “as required by state law.” But the insurer slipped in a new sentence more than a dozen pages later: Gene therapy was “not a Covered Service.”

Meanwhile, regional and national health plans began approving the drugs. Kaiser Permanente started covering them within months of the FDA’s approvals. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan — the state’s biggest health plan and Priority Health’s main competitor — paid for a cancer patient to receive CAR T-cell therapy in December 2017. (A spokesperson said in an email that the plan added coverage based on the treatments’ efficacy, without considering whether Michigan’s mandate applied. “We would have covered these drugs irrespective of the law,” she said.)

When the national Blue Cross Blue Shield Association made an announcement about CAR-T coverage later in 2018, employees at Priority Health forwarded it to one another. It was an I-told-you-so moment for Fox.

At a meeting that December, Fox made the case again that Priority Health should ask the state whether Michigan’s law required covering the new cancer treatments.

Forshee bristled. “You don’t trust our legal counsel?” he responded, according to Fox and another executive who attended.

His own temper rising, Fox considered what would happen if the company maintained its position. Patients who needed these therapies would likely die. Fox and his team would have to sign the denial letters, knowing the despair and anger they would sow.

After working at Priority Health for more than 18 years, Fox had once thought he’d retire there. He left that meeting certain he had to move on.

“Health plans have a right to make money; we’re providing a service,” Fox said. “But we have to do that honestly and fairly, putting patients first, not profits or premiums first. To me, that’s where we crossed the line.”

About seven months later, on a sticky night in July 2019, Forrest and Betty VanPatten were sipping beers with friends at the local club of the Fraternal Order of Eagles.

When they’d moved to Sparta, a small Michigan town known for its apple orchards, this was where they’d found community. The club had hosted countless charity raffles and fundraisers, including a “pink night” for the American Cancer Society for which Forrest squeezed into a hot-pink minidress Betty sewed for him. (There wasn’t much off-the-rack that could fit his almost 6-foot-8-inch frame.)

They were expecting biopsy results at any moment. Forrest had gone to the emergency room the previous weekend with intense pain. He’d made it through two previous bouts of lymphoma and suspected he was about to face another.

Forrest’s phone rang. It was the office of his primary oncologist, Dr. Brett Brinker. Oncologists meet hundreds of patients and their families, but Brinker had grown deeply fond of the VanPattens. Forrest was the guy who could talk to anyone, who made the party worth attending. Betty was his perfect foil. Their laughter and candor left a lasting impression.

The news was bad. Forrest had something called Richter’s transformation. It made his lymphoma significantly more aggressive and less likely to respond to conventional chemotherapy. After hanging up, Forrest typed Richter’s into his phone. Almost immediately, he proclaimed, “This is a death sentence.”

Betty needed to clear her head. She walked around the block, passing a restaurant where Forrest’s name was on the wall for completing a taco-eating challenge. When she got back, she urged Forrest to snap out of his defeatism.

He had just celebrated his 50th birthday and was determined to be around for his 51st. His kids, Donovan, 23, and Madison, 22, were in serious relationships, and he wanted to be there for their weddings.

“So we went in and got a game plan,” Betty said. Forrest would begin with chemotherapy, and, if the cancer went into remission, they would try for a stem cell transplant. If the cancer didn’t go into remission, Brinker made it clear they weren’t out of options. He told them about CAR-T.

It felt reassuring at the time.

By January 2020, CAR-T was all they had left. Brinker said he thought the treatment could at least bring Forrest’s disease under control for a few years. “It’s hard to use the word ‘cure’ when it’s acting like that,” he said of Forrest’s cancer. But if they won some extra time, he said, “there’s always something in the wings you can hope for.”

On Jan. 28, Williams, the doctor who ran the transplant program, worked with her team to submit a request for coverage to Priority Health. Williams knew the company’s policy on CAR-T but thought the insurer might relent when faced with an actual patient who was certain to die without the treatment. Plus, by that point, the federal government was covering the therapies for Medicare patients, and insurers often follow its lead.

Knowing it could take weeks to grow the cells used in the treatment, his doctors prepared to extract his white blood cells. “These are diseases where we don’t have a lot of time to waste,” Williams said.

Then Williams’ office found out that Priority Health had denied the request. Forrest’s doctors appealed but were turned down again, prompting Forrest to throw the tissue box at the wall.

Williams felt it, too. “I was deflated. I was angry,” she recalled. “We kept trying to work it out, and we kept hitting roadblocks.”

The VanPattens didn’t have the money to pay out of pocket, and Forrest didn’t want to saddle his family with medical debt. His medical team filed a third and final appeal, this one to an independent reviewer.

As that went forward, the VanPattens received a letter from Priority Health explaining its reasons for denying Forrest’s treatment. CAR-T cell therapy “is not a covered benefit,” and “therefore, we are unable to approve this request,” the letter stated. Somehow, seeing the words in writing conveyed a different finality, sending Forrest into a downward spiral.

“Everybody deserves the chance of fighting,” Betty said. “Once you take somebody’s hope away, you kill them — you really, really do. It was evident with him. He was defeated, and he had never been defeated in his life, and that was hard to watch.”

Their son, Donovan, took to social media to blast Priority Health for its decision, hoping to shame the company into a last-minute about-face. He included a screenshot of a text message from Forrest, who knew his insurer was an outlier. “It should be noted that Blue Cross and Blue Shield of MI pays for Car T Cell!” it read.

A reporter for Fox 17, a local TV news station, interviewed Forrest on Feb. 13 in the suede recliner he’d long claimed as his chair in the family’s living room.

“I feel like I’m being ignored,” he said, tears streaming down his face. “Left out to die, basically.”

Days later, Forrest was back in Butterworth Hospital with shortness of breath. “He is in acute distress,” an emergency room doctor noted when he was admitted.

The following night, his heart stopped beating. Betty retreated to the back of the room as doctors and nurses swarmed in. Donovan sat in a chair outside, his head in his hands.

Madison raced through Grand Rapids’ snow-covered streets to join them. When she reached her father’s room, a member of the medical team was still pushing down on his chest. But, she recalled, “it was clear he wasn’t there anymore.” The family told his doctors to end the resuscitation effort.

Forrest died on Feb. 17, before the independent medical reviewer had a chance to weigh in. Three weeks had passed since Williams and her team had asked Priority Health to cover the therapy.

Williams said that if Priority Health had approved the first request, Forrest could have received the infusion. It’s unknowable whether the treatment would have given him more time, she said, but if he’d had that chance, “anything is possible.”

Not long after Forrest died, his family received a handwritten card from a clinical coordinator who cared for him.

“I am so so so sad that we didn’t get the chance to put the rest of our plan into motion,” she wrote. “In honor of your kind (+very funny) husband, dad, friend, I promise to continue to push for Priority Health to cover CAR-T and to bring hope to all who need it.”

In Priority Health’s statement, Geary, the spokesperson, wrote that the company began covering the therapy “after extensive clinical work improved the treatment.” The company would not say when it began paying for the treatment or whether Forrest’s death influenced its decision.

“It is devastating when a disease takes a member’s life,” the statement said. “We recognize the deep pain of losing someone you love.”

To former state Sen. Joe Schwarz, now 86 and retired, the story of Priority Health and Forrest VanPatten is a painful echo of a problem he thought he’d fixed.

More than 30 years ago, Schwarz helped write the Michigan law requiring insurers to pay for cancer drugs. Schwarz, a physician, still recalls what drove him to action: Insurance companies were refusing to pay for drugs given to make chemotherapy more effective, arguing they weren’t themselves chemotherapy. An op-ed in the Wall Street Journal by the head of the Association of Community Cancer Centers confirmed that insurers nationwide were denying coverage for cancer patients.

At a Senate hearing, Schwarz accused health plans of abandoning their policyholders based on a “play on words.” When ProPublica told Schwarz about Priority Health’s gene-therapy argument, he let out a mirthless “hah,” scoffing at the wordplay.

“You shouldn’t split hairs between the term gene therapy and the term chemotherapy or the term radiation therapy or the term surgical therapy,” he said. “They’re all cancer therapies and they should all be covered.”

ProPublica gave Michigan’s Department of Insurance and Financial Services a detailed description of VanPatten’s case, as well as Priority Health’s contention that it didn’t have to cover CAR T-cell cancer therapies. We asked if Priority Health broke the state law on cancer treatments. Laura Hall, the department’s communications director, wouldn’t say. The agency can investigate if it spots a pattern of improper denials, but “in general,” she said, it only acts if a patient or their representative files a complaint.

The VanPattens didn’t do that. And they didn’t know about the Michigan law until ProPublica told them about it.

In the months after her husband died, Betty VanPatten was too weighed down by grief and anger to tangle with Priority Health through state insurance regulators. The days were a blur. Donovan and his partner, McKenzie, moved in with Betty, who threw herself into her job.

“I’d get up at 4, and I’d have my laptop and I just worked until about 9 or 10 o’clock,” Betty said. “And a lot of times I’d just sit there and the tears are just running down my face.”

The VanPattens still struggle with the sense that Forrest suffered an injustice and that Priority Health got away with it.

“They lost sight of the patient,” Betty said at a family dinner this July. Madison agreed.

“Insurance is meant to protect people,” she said, “not to make them fight through the last day to get what they should.”