Published on Apr 09, 2025

Data broker LiveRamp Holdings, Inc. (RAMP) operates a vast digital marketplace that exchanges the personal information of hundreds of millions of individuals grouped into highly specific audience “segments”—many of which include potentially sensitive information denoting everything from a consumer’s religious beliefs and ethnicity to their health and financial status, a Capitol Forum investigation has found.

LiveRamp’s Data Marketplace even lists hundreds of commercially available segments tied to U.S. military personnel, their families, and defense contractors for sale, a practice experts say poses a national security risk, especially since LiveRamp assigns individuals a unique identifier called a “RampID” that can be used to target specific devices and is associated with a complete set of online and offline information about a consumer.

The Capitol Forum obtained a list of more than 500,000 Data Marketplace segments—all uploaded by third-party “data providers” which partner with LiveRamp to sell their datasets—some of which offer targeting of active-duty military members broken down by service branch, residents of Fort Bragg (home to the U.S. Army Special Operations Command) and other military bases, “[e]mployee devices at companies that manufacture military equipment,” and individuals “known to work” at major defense contractors like Lockheed Martin (LMT), Northrop Grumman (NOC), and Raytheon (RTX).

Data providers listing military personnel segments available for sale in the Marketplace included major credit reporting agencies Experian (EXPN.L) and TransUnion (TRU) as well as data analytics companies like LexisNexis (RELX).

Other Marketplace segments promise access to leaders in the government and public service sectors, such as “Commissioners, Mayors, Police Officers, [and] Military Personnel,” while data broker StatSocial touted a segment claiming to reach “executives, managers, contractors, and all decision-makers working within the military and defense aerospace industry, engaging with content around” specific weapons systems including airplanes, rotorcraft, missiles, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and aircraft carriers.

“We’re not dealing with data that’s abstracted, but exactly the kind of thing you’d want if you’re a [Chinese] MSS or [Russian] GRU officer, looking at who are we going to hack or who are we going to approach, based on their position in the U.S. government,” Justin Sherman, CEO of Global Cyber Strategies and a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council said. “These are exactly the kinds of segments that a foreign adversary would be interested in.”

Despite LiveRamp’s Data Marketplace Data Policy ostensibly prohibiting providers from selling segments that target certain kinds of sensitive data, including data “defined as ‘sensitive’ (or any analogous term) by an applicable privacy law” and segments pertaining to specific health-related topics including abortion, reproductive health, sexual orientation, and information “describing any individual’s known health or medical condition(s), including Protected Health Information (PHI),” The Capitol Forum found numerous segments that potentially violate these terms.

Data provider Adstra, for instance, offers marketgoers 90 segments identifying individuals “likely to have” specific health conditions, from asthma and spinal arthritis to diabetes and Parkinson’s disease. Thousands of other segments group consumers by their specific race, ethnicity, or country of origin, while some data brokers tie demographic data together with political leanings, financial status, and other attributes to create hyper-specific groups segments like “Hispanic voters that are more likely to agree that state legislators should move toward making abortion illegal” or “Primarily Asians in geographies with the most hate crimes.”

Such segments are ripe for abuse by government or private actors pushing for targeted deportations, voter disenfranchisement and disinformation, or other forms of surveillance, says Clarence Okoh, the Senior Associate at the Georgetown Law Center on Privacy and Technology and a former NAACP Legal Defense Fund attorney.

“We saw it in 2024, with the Russian government using forms of targeted disinformation and terror to send these false bomb threats to predominantly African American precincts,” Okoh said. “The possibilities are really endless…This is literally our democracy up for sale in this moment.”

In an email to The Capitol Forum, StatSocial President Michael Hussey said that “StatSocial’s audience segments available on LiveRamp’s Data Marketplace are aggregated, anonymized groups created from publicly available social media audience data,” including the one reaching “executives, managers, contractors, and all decision-makers working within the military and defense aerospace industry,” and that “StatSocial does not create, sell, or otherwise distribute segments specifically targeting active-duty U.S. military personnel or contractors based on non-public or sensitive data.” Click here to read the full statement.

Adstra’s Chief Privacy Officer and General Counsel said in an email that “Adstra maintains rigorous compliance with all applicable United States federal and state privacy laws, regulations, and statutory obligations, as well as the contractual and policy frameworks governing our participation in LiveRamp’s Data Marketplace, including, without limitation, the Marketplace Data Policy.”

An Experian spokesperson said in an email that “Experian remains committed to consumer privacy. We comply with the data protection laws in all the states we operate.”

TransUnion said in an emailed statement that “TransUnion protects its consumer data for marketing purposes by [pseudonymizing] identities, including within segments related to service members. TransUnion also governs its partners’ use of consumer data, requiring practices to prevent reidentification.”

A LexisNexis spokesperson said in an email that “The information available on LiveRamp that is provided by us is anonymized, aggregated, and cannot be used to identify or target any particular individual or household. It is used solely to support the delivery of content or messaging that may be relevant to broader audience interests. We require recipients of our information to adhere to strict privacy practices.”

LiveRamp did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

LiveRamp provides platform to hundreds of data brokers for selling sensitive consumer segments. LiveRamp sits at the nexus of the digital advertising ecosystem and a multi-billion-dollar data broker industry that amasses thousands of attributes per individual consumer based on online and offline activity, public records, and other third-party datasets to build detailed audience segments that enable targeted advertising campaigns.

“To make every experience relevant…you need to activate those interactions with consumers with data,” LiveRamp CEO Scott Howe said in a 2018 interview. “What LiveRamp has done is, they’ve gone and integrated all of the world’s data providers, linked that data to all of the world’s people, and then in turn, link that to built [sic] connections to all of the world’s use cases.”

Rather than conducting targeted advertising itself, the company stitches together any disparate data points a client has collected about an individual—like their physical address, Facebook username, personal device IDs, and tracking pixels detailing their internet search history—around a single pseudonymous identifier known as a “RampID,” which offers a “360-degree view” of a consumer and is connected to the segments sold on the LiveRamp’s Data Marketplace.

Supporting “all industries and encompassing all types of data,” the Data Marketplace hosts third-party audience segments uploaded by more than 200 different providers, which have data and revenue-sharing agreements in place with LiveRamp. The Marketplace serves as a mass data amalgamator, a one-stop platform where other data buyers, companies, and leading global brands can browse and purchase segments to help “improve [advertising] targeting, measurement, and customer intelligence.”

“Data accessed through the LiveRamp Data Marketplace is connected via RampID and is utilized to enrich our customers’ first-party data and can be leveraged across technology and media platforms, agencies, analytics environments, and TV partners,” LiveRamp says in its latest annual filing.

LiveRamp integrations also enable data sellers to distribute Data Marketplace segments to Google (GOOG)’s public third-party data marketplaces Display & Video 360 (DV360) and Google Ad Manager as well as Amazon (AMZN)’s own Data Exchange, provided sellers adhere to the other companies’ data restrictions. However, as reported in February by Wired, DV360 also hosts “hundreds if not thousands” of sensitive audience segments that are seemingly banned under Google’s public data policies.

“Google’s policies prohibit audience targeting based on sensitive information like health conditions, and we take action when we detect policy violations,” a Google spokesperson said in an email.

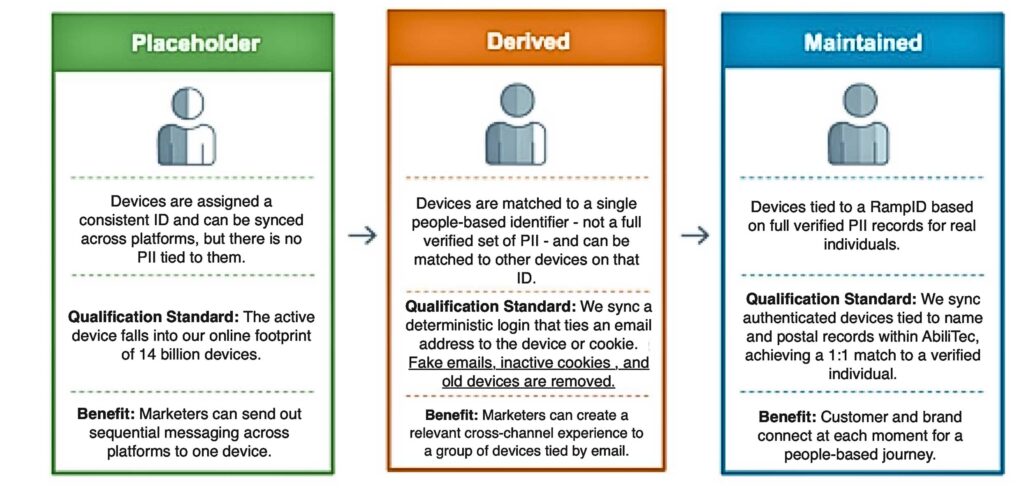

LiveRamp’s identity graph consists of “maintained” RampIDs—meaning the ID represents an individual that LiveRamp “fully recognizes” and can be matched with multiple pieces of personally-identifiable information. The company says it can send clients “files that map cookies, user IDs, and mobile devices to RampIDs on a regular cadence.”

Source: https://docs.liveramp.com/connect/en/interpreting-rampid,-liveramp-s-people-based-identifier.html

While adtech companies and data brokers often claim alphanumeric ad-based identifiers like RampIDs are “pseudonymous” to protect consumers’ identity, it is “alarmingly easy” to take datasets without names or emails and “re-identify” specific people, according to Sherman.

Even by LiveRamp’s own admission in its Product and Service Privacy Notice, mobile advertising IDs constitute a form of personal information that is “reasonably capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked with a particular consumer or device.”

“Re-identification is easier and easier already,” Sherman said. “It’s even easier when you have a platform that sells a bunch of datasets next to each other and creates an identifier to tie people together across all of those datasets.”

Marketplace military segments could be used to target, surveil U.S. service members. Experts say that by centralizing segments that could potentially be used to identify millions of active-duty military members alongside other pieces of sensitive information, LiveRamp increases the risks posed if a foreign adversary accesses its data.

“The ability to correlate different huge databases is the key to intelligence,” says James Andrew Lewis, a Senior Vice President at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and a former member of the U.S. Foreign Service and Senior Executive Service, where he worked on cybersecurity, encryption, and high-tech exports to China. “Data brokers are such an easy way in… It’s not James Bond, it’s more like advertising stood on its head.”

Other companies have unwittingly exposed sensitive military intelligence by creating easy-to-access or even public datasets—like fitness app Strava, which in late 2017 released a global heat map of users’ exercise routes that revealed the location and layout of military bases. LiveRamp’s marketplace creates a unified platform for purchasing military data that can be associated with other personal information, such as gambling habits or unstable finances, and could prove useful from an intelligence perspective when deciding which individuals or groups to monitor or attempt to influence.

Data Marketplace data provider Verisk (VRSK), for example, sells the segment “Single in Suburbia,” which targets individuals who are “single without children in the household, living in suburban rentals that are likely located near a military base.”

“These Associate’s degree holders are enjoying careers in the armed forces, law enforcement and administration,” the segment description continues. “They like playing the lottery, and gambling in general, and can be seen zooming around town on their motorcycles. Although their limited budget goes towards necessities like transportation, food & beverages and personal care, ‘Single in Suburbia’ also have enough left over to purchase low-ticket home furnishings or perhaps a new toy for their household pet.”

Verisk did not respond to a request for comment.

The Marketplace lists the estimated number of individual cookies and iOS and Android systems a given segment will reach—450,000; 1.2 million; and 1.3 million, respectively, in the case of “Single in Suburbia”—along with any use case restrictions for advertising to a specific segment. Only three of the more than 220 military-related segments reviewed by The Capitol Forum said they required specific authorization from LiveRamp to use and all but five of the segments allowed for digital ad targeting.

“This is a national security risk,” Sara Geoghegan, Senior Counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), said. “These companies do not employ enough sufficient safeguards to adequately protect the information that they collect and retain.”

A complaint filed in January by EPIC and the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL) calls on the FTC to investigate whether Google’s real-time bidding system—which enables advertisers to bid on ad impressions in real time—violates the Protecting Americans’ Data from Foreign Adversaries Act (PADFAA) and Section 5 of the FTC Act by allegedly exposing Americans’ sensitive information to foreign and non-state actors.

While LiveRamp states it does not provide RampID mapping files—which can be used to map an external identifier like a cookie, mobile ad ID, or CTV ID to an individual RampID—to “APAC [Asia-Pacific] markets,” privacy experts say many workarounds exist to potentially link a RampID with an individual’s identifying information.

Once a military segment is obtained, for instance, a bad actor could drive targeted users to an online form asking for their name or email address, thereby reidentifying the segment’s data. Foreign adversaries or firms could also try using a VPN or shell companies based abroad—tactics commonly used by money laundering operations—to bypass any geographical data sharing restrictions.

“Spies aren’t exactly known to put on name tags,” Sherman said. “The needless proliferation of this data is hugely damaging. We’re not even talking about where it goes once it’s out of the LiveRamp system.”

Other descriptions of specific military-related segments found by The Capitol Forum in the Data Marketplace included:

Medical and health-related segments. Although LiveRamp says it prohibits data providers from selling segments related to certain health topics, the company notes that it does permit segments “consisting exclusively of opinions about the health-related topics listed,” so long as the audiences “do not infer the person has or has had the condition.”

Labeling segments by consumers’ interest in a sensitive topic, like reproductive rights or a specific religion, is a common tactic employed by data brokers to comply with such policies, says Arielle Garcia, the Chief Operating Officer of digital advertising watchdog Check My Ads.

Before going live on the Marketplace, a segment has to “be reviewed and receive privacy and business approval,” according to LiveRamp, which adds that most segments are reviewed and approved “within 1-2 business days.” On one Marketplace help page, LiveRamp lists guidelines for segment approval, telling data providers to avoid “definitive” language when submitting segment descriptions for review.

Rather than saying “Consumer is interested in purchasing a new Ford F150,” LiveRamp suggests a less definitive version: “Consumer is likely interested in purchasing a new Ford F150” [emphasis in original].

“It’s very easy to have proxy audiences,” Garcia said. “Not just an interest in a particular disease, but what about caretakers for someone with a particular disease? [That’s] arguably more of a gray area from a compliance perspective, but is the potential for data abuse any less in those in those circumstances, or is it kind of just a workaround?”

Despite LiveRamp’s Marketplace policies allowing for “opinions” but not information “describing any individual’s known health or medical condition(s),” dozens of available segments still labeled individuals by their specific conditions and chronic diseases or treatment regimens.

Data broker Epsilon, which entered into a $150 million settlement with the Department of Justice in 2021 for selling millions of Americans’ data to perpetrators of elder fraud schemes, lists over 30 segments in the Data Marketplace claiming to identify people who use certain treatment regimens (such as “adult diapers for their bladder leakage”) and take medications to treat specific conditions like arthritis and high blood pressure. Epsilon did not provide comment for this story.

Epsilon’s data feeds into the health unit of its parent company, French advertising giant Publicis Groupe S.A. (PUB), which agreed to pay $350 million last year as part of a national settlement over the company’s role developing marketing strategies for Purdue Pharma opioids.

“It feels like a deeper, more systemic cultural gap within Publicis as a whole, that these issues around data abuse and the potential resulting harm don’t seem to be taken very seriously,” Garcia said.

Descriptions of segments offered by various providers relating to consumers’ specific health conditions and treatment preferences included:

Race and ethnicity segments. The Capitol Forum identified nearly 2,000 segments in the Marketplace that claimed to target individuals and households from specific religious backgrounds and ethnic origins, from Judaism and Islam to Albania and Wales. Like other categories of personal information, some race and ethnicity-specific segments included other potentially sensitive attributes in their descriptions, including:

Political viewpoint segments. Hundreds of Marketplace segments can be used to target consumers’ political leanings. Many go beyond simply listing a likely voter’s political party or Congressional district and instead pinpoint stances on specific political issues, from abortion to the Black Lives Matter movement.

One segment purported to target an estimated 9.8 million iOS systems belonging to “Primarily Asians in geographies with the most hate crimes” who “strive for a just and inclusive society where everyone, regardless of their race or ethnicity, can live without fear.”

Another segment named “Disenfranchised American Dream” helps data buyers reach up to 87 million iOS and 59 million Android systems of middle-class “mostly white and less educated people unable to live the American Dream their parents enjoyed” who “work longer hours for less pay and rarely spend time with their families.”

“This type of information can do all kinds of horrific things to folks,” Okoh said. “The ability to do targeted voter disenfranchisement, targeted voter disinformation, to try and make it even [more] difficult for folks to be able to make sense of what’s happening in the world around them.”

Examples of Marketplace segments with names and descriptions tying an individuals’ political views to other pieces of potentially sensitive information included:

LiveRamp provides identity resolution services as states crack down on collection of sensitive data. In addition to hosting the Data Marketplace, LiveRamp also offers its own “identity resolution” services, “connecting the dots between consumers’ digital footprints to give the full picture of their online behavior across devices, channels, and touchpoints.” With more browsers blocking use of third-party cookies—small text files which enable tracking of users across the web—LiveRamp touts its ability to link together disparate pieces of data tied to individual consumers on behalf of clients.

The company sources consumers’ personal information in a variety of ways, from its own first and third-party cookies placed on external websites to data shared or bought from a partner. A class action lawsuit in Florida federal court alleges LiveRamp and a number of other companies placed cookies on cannabis retailer Trulieve’s (TRUL.CN) website, potentially gleaning insights into individuals’ use of medical marijuana.

Another proposed class action filed San Francisco federal court in January alleges LiveRamp’s databases contain the personal information of “virtually every adult in the United States” and that plaintiffs had “no reasonable or practical basis upon which they could legally consent to LiveRamp’s surveillance.” In its motion to dismiss filed March 28, LiveRamp claimed that plaintiffs lacked legal standing and that the company “primarily provides services that enable advertisers to deliver targeted ads across digital platforms, a function that helps keep the internet free.”

While LiveRamp says in its motion that it “uses multiple security measures to ‘ensure [that] RampIDs cannot be directly tied back to [personally identifiable information],’” the company’s identity resolution practices depend on tying personal information to an individual its clients wish to target.

“[B]y by associating an email address with a cookie, LiveRamp and third parties can link your browsing activity across different websites and other applications and services to your specific device associated with the email address, identifying the user behind the device,” LiveRamp says in its Product and Service Privacy Notice.

“This means that, even when browsing unrelated sites, your online activity can be connected to you for advertising and other marketing-related purposes, including email marketing and offline advertising. As technological capabilities increase, the ability of any consumer to maintain a state of not being known online will inevitably decline,” the policy continues.

“I have never encountered or heard such brash language in an actual public-facing privacy statement,” said Okoh, who noted such far-reaching data collection practices are increasingly coming under fire from several state-level privacy laws.

The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA), for instance, defines “sensitive data” as “personal data revealing racial or ethnic origin, religious beliefs, a mental or physical health condition or diagnosis, sex life or sexual orientation, or citizenship or citizenship status,” along with biometric data or data acquired from a known child.

Under the law, a data controller cannot process a consumer’s sensitive data without first obtaining consent, meaning a “clear, affirmative action” and not “acceptance of a general or broad terms of use or similar document that contains descriptions of personal data processing along with other, unrelated information.”

“What average person knows that LiveRamp exists?” Garcia said. “Most people are not interacting directly with these companies, not to their knowledge.”