Published on Apr 28, 2022

MultiPlan’s (MPLN) products for health plans fall under two umbrellas—a preferred provider organization (PPO) network product and products related to payment editing, negotiating, and repricing of healthcare claims.

The Capitol Forum has previously reported about the company’s editing, negotiating, and repricing services.

MultiPlan’s PPO product lets health plans rent Multiplan’s networks as a primary network or as a complementary “wrap” network to extend a plan’s established network.

For its PPO product, MultiPlan contracts with healthcare providers to set agreed-upon payment rates for the providers’ services. The providers gain access to members of health plans that are MultiPlan clients and agree not to balance bill the members. Separately, MultiPlan contracts with health plans so the plan members can receive services from MultiPlan PPO providers at the rates agreed to in the contracts between MultiPlan and the providers.

But, according to the Capitol Forum’s ongoing investigation, MultiPlan allows clients to disregard the PPO contractual rates and pay claims at lower rates. MultiPlan’s clients can choose this option after services have been rendered and on a claim-by-claim basis. The provider and the patient are kept in the dark until after the claim has been processed. If the plan decides to pay less, the transaction shifts from an in-MultiPlan-network service to one that is considered out-of-network, meaning providers are no longer prohibited from balance billing and the patient may be surprised by unexpected balance bills.

MultiPlan’s PPO product is essentially a “maybe-you’re-in-network” PPO offering, although providers and patients think that services are being offered in-network.

MultiPlan’s strategy to let clients opt out of contractually agreed-upon rates was implemented, seemingly unilaterally, beginning in late 2015.

Does MultiPlan’s “maybe-you’re-in-network” PPO product violate the No Surprises Act? The US Department of Health and Human Services is set to implement a new rule under the No Surprises Act that will require providers and health plans to provide specific cost and payment breakdowns for the patient in advance of healthcare services. Such a rule would likely prohibit MultiPlan’s “maybe-you’re-in-network” PPO product, because patients getting treatment from “maybe-in-network” providers don’t find out information about the service—whether it was in network, the costs, co-pays, etc—until after the service is provided.

The No Surprises Act went into effect in January of this year, and companies are supposed to make good faith efforts to honor the law. But several provisions are not expected to be enforced until 2023 because HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra has not yet issued rules to implement those provisions, according to Jack Hoadley, Research Professor Emeritus in the Health Policy Institute of Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy.

Statement from Multiplan. A MultiPlan spokesperson provided the following statement:

“We stand behind our mission to deliver affordability, efficiency and fairness to the US healthcare system. Our solutions provide a strong value proposition to payors, health plan sponsors and members, as well as to providers. All of our pricing methodologies are fair, transparent and reasonable.

“MultiPlan has a diverse base of payor clients (and their customers) that access all or some of our network-based, analytics-based and payment and revenue integrity services to support a variety of plan configurations. This flexibility enables significant innovation, helping providers see more patients, and giving payors more tools to manage health care costs and in turn reduce their members’ out of pocket costs.

“Regardless of which out of network pricing methodology or methodologies our customers request that we use to price a claim, our pricing amounts are always recommendations to the healthcare payor. Clients ultimately decide what to pay the provider based on their benefit plan design and established payment policies.”

Analysis of Statement. MultiPlan, in its statement, appears to distance itself from responsibility by saying decision-making is left entirely up to clients that pay health claims. MultiPlan’s statement also does not directly address specific questions about MultiPlan’s PPO asked by The Capitol Forum.

MultiPlan PPO Networks Background

Health plans can rent MultiPlan’s network of providers as a primary network or as a complementary or “wrap” network.

MultiPlan clients pay a flat fee or a percentage of savings fee to access MultiPlan’s networks, according to the company’s recent annual filing.

MultiPlan’s primary networks. When a health plan does not have its own network of providers, MultiPlan’s PHCS network functions as a primary network for a flat fee. MultiPlan also says some Medicare Advantage and Medicaid plans “outsource some portion of their provider network development to MultiPlan.”

Multiplan’s complementary, or “wrap” networks. Plans that have their own established network use MultiPlan’s networks as a “complementary” or “wrap” network. Clients pay MultiPlan a percentage of savings fee to access the complementary network. But when a client opts a claim out of the network, the client pays nothing to MultiPlan.

The clients who use the complementary network most commonly include large commercial insurers; property and casualty (workers’ compensation and auto medical) carriers via their bill review vendors; Taft-Hartley (labor union bargaining agreement) plans, health system-owned plans, independent plans, and some third-party administrators who process claims for employer-funded plans. MultiPlan says in the filing that complementary networks operated “under the health plan’s out-of-network benefits, or otherwise can be accessed secondary to another network.”

Starting in 2015, MultiPlan intentionally undermined its participating provider agreements. Since at least 2011, some insurer clients were opting out of MultiPlan contracts on a claim-by-claim basis when they wanted to pay less than the rate in the agreements between providers and MultiPlan, according to provider correspondence with MultiPlan reviewed by The Capitol Forum. But the practice appears to have been a violation of the providers’ contracts with MultiPlan.

So, in 2015 MultiPlan quietly took a series of steps to unilaterally “update” providers’ contracts to give clients legal cover for ignoring MultiPlan’s participating provider agreements.

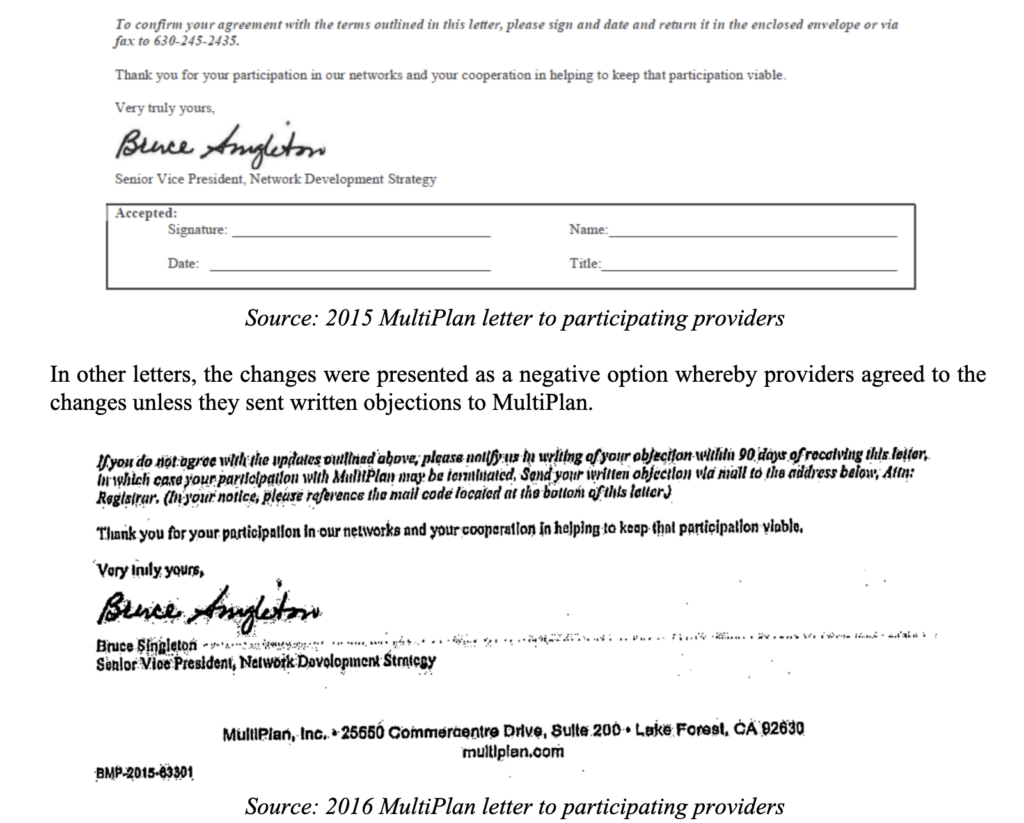

In letters sent to providers in late 2015 and early 2016, MultiPlan told providers that there were several conditions under which MultiPlan’s clients would not be obliged to honor the terms of providers’ MultiPlan network agreements. Most importantly, “If the benefit plan or reimbursement policy sets a maximum amount the plan will pay, the terms of your agreement may not apply to a specific claim if the agreed contract rate for that claim is above the maximum amount,” Bruce Singleton, MultiPlan senior vice president of network development strategy, wrote in the letter.

This change meant that if an insurer wanted to set a rate lower than a provider’s MultiPlan PPO contracted rate, the insurer could refuse to access the network, apply their own rate instead, and leave the patient with the rest of the bill. Providers and patients who were expecting the patient’s liability to be contingent upon the provider’s MultiPlan contractual rates would be in for a surprise if the health plan opted out of the network.

In some letters, Singleton gave the impression that providers could accept or reject the update because he asked providers to confirm their agreement with the terms outlined in the letter by signing off on the changes.

But MultiPlan imposed the changes regardless of whether providers rejected the changes or not, according to correspondence and other documents filed in several lawsuits against MultiPlan, reviewed by The Capitol Forum.

One of the facilities that explicitly rejected the changes was Sarasota County Public Hospital District, according to deposition testimony and exhibits presented during litigation the facility brought against MultiPlan and insurance carriers. “We are in receipt of a letter from MultiPlan in regards to changes in the agreement…We dispute this letter in its entirety,” the facility wrote to MultiPlan in January 2016.

MultiPlan implemented them anyway, according to Sarasota’s allegations. The case settled before trial.

In another lawsuit against MultiPlan, the attorney for a provider group who objected to the changes in Singleton’s letter questioned Singleton exhaustively about the letter during a deposition. Singleton explained during the deposition that the decision to send the letter originated with MultiPlan’s legal department which had tweaked the language in the letter for three to six months with input from the company’s network development and healthcare economics departments before it was sent to providers.

Singleton also testified that MultiPlan decided to send the letter to several thousand providers throughout the country whose charges were at or above 500% of Medicare’s rates. Singleton’s deposition was taken during litigation against MultiPlan by a New York bariatric surgical group. The facility lost in the lower court and has filed an appeal, which is pending.

Separately, in a deposition taken during the Sarasota litigation, MultiPlan executive Shawn McLaughlin testified that Singleton’s letter “was intended to be on the forefront of transparency, to let our providers know that there were changes happening with our clients that were going to happen whether they signed this letter or not, and this was an attempt to get acceptance from the provider community…”

In addition to the letters, MultiPlan also updated its template provider agreement in 2015 to include the new language, according to an exhibit filed in New York case. And, as Singleton noted in his letters, contemporaneous to sending providers the letter, MultiPlan revised its “administrative handbook(s) to include the same updates and clarifications.”

Further, in addition to the letters, the template, and the handbooks, MultiPlan began including new language in amendments to its provider contracts.

According to documents filed in recent lawsuits reviewed by The Capitol Forum, Multiplan amended PPO providers’ contracts, specifically related to Multiplan’s client access to complementary networks.

MultiPlan has been relying on the changes detailed in the letter, the handbook, and the contract amendments as defenses to allegations of underpayment in several recent lawsuits brought by doctors and facilities, reviewed by The Capitol Forum.

Many providers, ranging from large and well-funded companies like TeamHealth to small providers’ offices and facilities, have signed off on MultiPlan’s letters or contract amendments without fully grasping the implications.

Expert discusses how the No Surprises Act addresses MultiPlan’s “maybe-you’re-in-network” PPO Product. Jack Hoadley, a research professor emeritus in the Health Policy Institute of Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, explained how the No Surprises Act may cover MultiPlan’s misleading conduct in its PPO plans:

“From the point of view as consumer protection there is a new element with the No Surprises Act that went into effect at the beginning of this year.

“There is a lot of depth in this law. I think some of the details have flown a bit under the radar. With implementation starting this past January, we’ve seen a significant amount of publicity around the core protections about emergencies and being billed by out-of-network providers who see patients at in-network hospitals. Over the next year, as we get to more rulemaking and the full enforcement in 2023, I do think we are going to continue to hear more about some of these other provisions. I think there is a lot more that consumers, providers, and insurers are going to need to understand so that the consumers benefit, and the providers and insurers stay in compliance with the law.

“The No Surprises Act [NSA] is the law, but some provisions are not going to be actively enforced yet. There’s delayed enforcement for some areas of the law.

“For services where the NSA’s balance billing prohibitions do not apply, patients are now eligible, under the NSA, to get pre-service advance explanation of benefits [AEOBs]. Providers are required to provide information on what it will cost the consumer out-of-pocket in advance of the service.

“So, that’s going to have an effect on this notion of insurers being able to change the rules after the claim is submitted because if the patient gets that AEOB notice and then it changes, it will have an impact on the patient as well as the provider.

“The AEOB provision has not been fully implemented in the sense that the rules have not been written on this for insured patients. There are rules for AEOBs for uninsured patients. As far as rules for insured patients, there is rulemaking to come later this year but the law itself is already in effect and insurers are supposed to make good faith efforts to comply with this. It won’t be enforced until 2023.

“The idea for AEOBs is that a provider, who is scheduling a service with a patient—whether it’s in a facility or in a provider’s office or in-network or out-of-network—has to submit information to the health plan. The plan is supposed to send written information about the financial breakdown of what the insurer will pay, what the provider will be paid by the insurer, and the amount the provider is allowed to charge the patient in cost sharing. The intent is that patients can make an informed decision and decide if they want to try to find a more affordable option.”

The intent of this provision, Dr. Hoadley explained, is that patients are provided with transparency and actual dollar figures, not some vague references to “usual and customary,” or “based on prevailing rate,” or “proprietary database calculations.” But he emphasized again, “until the rulemaking is done, the details of what exactly will be required hasn’t been formalized yet. The intent of this law is that, before a service is provided, patients will know what their financial obligation will be after their insurance is taken into account.”

Dr. Hoadley continued describing the intent behind the AEOB provision:

“It’s a good faith estimate, it’s not that the insurer is committing to the estimate. But certainly, there are going to be issues if a plan wants to decide differently after a service has been provided and say, ‘Oh no, we are no longer treating this the way we were in the AEOB. So, instead of your bill being $425, it’s going to be $800.’ There’s not a specific legal remedy in the law, but I think it will certainly put some additional leverage on the situation to have the financials settled before the service is delivered.

“There is an enforcement aspect to this in the law but, at least initially, it deals with whether the AEOB was provided or not.

“This provision will apply to employer funded plans and employer fully insured plans as well as plans purchased on the individual market.

“I would hope that the rulemaking will address what happens if circumstances change. Of course, there are legitimate reasons for an increase in out-of-pocket costs actually owed compared to the AEOB, such as scheduling the service in December and the patient had met their deductible but there is a delay and the service actually takes place in January when the deductible starts over from zero because it’s a new plan year. Another reason could be if complications arose during a procedure.

“But as a policy person, if a plan sends an AEOB based on the assumption that a service would be treated as in MultiPlan’s network and then they changed their mind after the service was provided, I certainly as a patient would be in an uproar. I would hope that the rulemaking would address that and make it clear that is not a reasonable adjustment.

“The whole idea is to give patients the chance to know what they’ll owe. And if they think it’s more than it ought to be, then they have the chance to go talk to other providers to compare prices. This provision in the NSA is about a well-informed consumer—whether you are going to comparison shop or just be prepared for the amount you are going to be responsible for paying.

“So, while this provision wasn’t written with the MultiPlan behaviors in mind, it certainly is written to the basic idea of no surprises. Mostly we think of that related to balance billing in emergencies or hospitals, but, as the lawmakers wrote this, it was about other kinds of situations too.”

Dr. Hoadley also discussed another provision in the No Surprises Act regarding network accuracy and incorrect provider information:

“What do you do if a health plan’s provider directory says Dr. Smith is in the network and it turns out that Dr. Smith is not in the network?

“The NSA limits cost sharing to the amount that would have been applied if the provider was in network if the enrollee demonstrates that they relied on the health plan’s provider directory and that information turned out to be incorrect. In this situation, the patient will only owe their in-network cost sharing.

“So, if MultiPlan lists a provider as in network and you make a decision based on that, then you as the consumer should be protected. It doesn’t speak to what the provider will get but the consumer should be protected.”