Published on Feb 04, 2022

Oak Street Health (OSH), an operator of primary care clinics for Medicare beneficiaries, appears to encourage physicians to diagnose chronic conditions in their patients even when the diagnosis may not be appropriate, according to internal company documents reviewed by The Capitol Forum and interviews with former medical staff at the company.

The internal documents also indicate that Oak Street Health physicians are diagnosing certain chronic conditions at substantially higher rates than the average for Medicare beneficiaries, with the company suggesting ways to further increase those diagnosis rates.

The higher rates of diagnosis are important because Oak Street Health largely works with Medicare Advantage program. Under the Medicare Advantage plan, Medicare pays companies more money for caring for sicker patients, a structure that critics have said incentivizes companies to make their patients appear sicker in order to increase reimbursement.

A spokesperson for Oak Street Health denied that the diagnosis rates were inappropriately high when compared to Medicare averages, stating that “a large percentage of our patients are dual eligible for Medicare and Medicaid and not representative of the ‘averages’ you cite.” However, they declined to provide more appropriate data for comparison.

The spokesperson also denied that the company pressured medical staff to diagnose certain conditions. However, former physicians, nurse practitioners, and medical coders have previously told The Capitol Forum that they did feel pressured to diagnose patients with conditions that would increase their risk adjustment scores, the metric used by Medicare to calculate a patient’s medical complexity.

The former employees also said that the company had them seek out and diagnose certain conditions with high risk adjustments, and that the basis for those diagnoses was often tenuous. Some of the conditions mentioned by former providers as a focus of Oak Street Health included congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary fibrosis.

Internal Oak Street Health documents suggest that this pressure may have had a large impact on the diagnosis rates for several of those risk adjusting conditions.

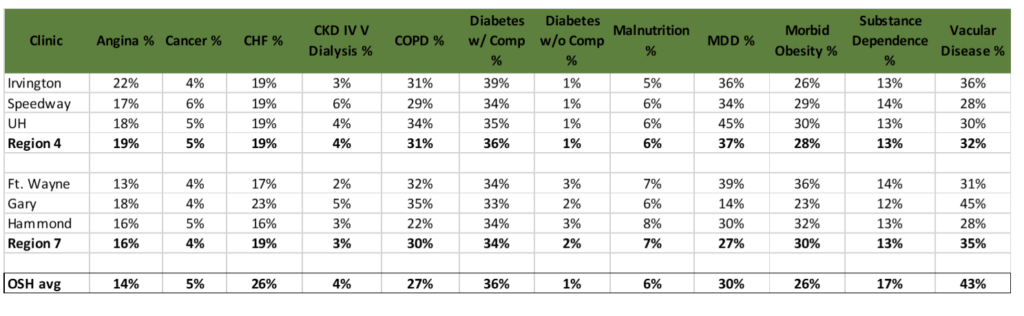

A former employee in Indiana sent The Capitol Forum a 2018 chart produced by Oak Street Health that detailed prevalence rates of twelve chronic conditions at each clinic in the state. The Capitol Forum has reproduced the data from the chart in order to protect the identity of the employee:

The chart compares the prevalence rates of each clinic with Oak Street Health’s company-wide average, which are far above the national prevalence rates among Medicare beneficiaries for each chronic condition.

For example, according to CMS’ Chronic Conditions Warehouse, prevalence rates among Medicare beneficiaries for heart failure and COPD were 14.6 and 11.7 percent, respectively. At Oak Street Health, prevalence rates for those conditions were 26 and 27 percent, respectively.

Oak Street Health’s prevalence rate for vascular disease (43 percent) was also much higher than the national average (11.8 percent) for Medicare beneficiaries, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

In the opinion of one former physician at Oak Street Health, one cause for the high rate of vascular disease is the company’s training guidelines that state that patients with an Ankle Brachial Index of up to .99 should be considered as having vascular disease. According to the physician, an ABI of .9 to .99 would be classified as borderline at most other practices.

Dr. Rick Gilfillan, the former director of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation at CMS, reviewed the chart and said that, while the diagnosis rates were much higher than they should be, he was unfortunately not surprised given the incentives for Medicare Advantage companies to game risk scores. Dr. Gilfillan, however, said that he was surprised by the disparity between diabetic patients diagnosed with chronic complications (36 percent) and diabetic patients diagnosed without chronic complications (1 percent).

“It takes years to develop chronic complications from your diabetes,” he explained, “By definition, there should be a significant number of diabetics without chronic complications.”

A diagnosis of diabetes with chronic complications would garner an additional roughly $2,400, on average, from Medicare per patient per year over a diagnosis of diabetes without chronic complications.

Asked about the chart, the spokesperson for Oak Street Health said that the chart “does not show Oak Street company-wide average prevalence rates,” but declined to say what the chart actually shows or its purpose. However, the former employee who sent the chart to The Capitol Forum stated that the “OSH avg” rates at the bottom of the chart were the company-wide average.

The spokesperson also declined to answer specific questions regarding the rates of chronic conditions at Oak Street Health, including questions regarding the disparity between the two groups of diabetes diagnoses.

Documents recommend ways to find and diagnose more conditions. One purpose of the chart may be to highlight where a clinic is underperforming in diagnosing chronic conditions relative to the rest of Oak Street Health. Accompanying the chart is a document highlighting “opportunities” to bring some of the clinic’s diagnosis rates in line with the rest of the company.

“Prevalence data, when compared with OSH prevalence rates, suggest there are opportunities for discussion with CHF [congestive heart failure] & vascular disease,” the summary reads. A diagnosis of congestive heart failure and vascular disease could net, on average, roughly $2,370 and $3,660 per patient per year, respectively.

These opportunities included “Pop[ulation] Health investigating methods to better identify & retrieve pertinent medical records.”

Former medical providers at Oak Street Health have told The Capitol Forum that employees would routinely comb through old medical records and exams to find any indication of disease. For example, providers said they were often presented with old chest X-Rays of patients that showed slight scarring, known as granuloma, and asked to diagnose pulmonary fibrosis, a diagnosis that the physicians felt was not justified solely by the existence of granuloma.

Other opportunities to increase diagnosis rates for CHF included “Prelim[inary] Discussions around diagnostic equip. (mobile echos) or physician partnerships.”

Another document titled “Risk Adjustment Plan for 2018” also detailed several methods that clinic staff could use to find and document risk adjusting conditions.

These methods include a monthly, two-hour review session for each provider to “address all suspected conditions on the care registries (accepted, denied, follow-up).”

For medical assistants, the plan says that they should “Complete in-clinic testing/screening” which includes conducting tests such as spirometry, QuantaFlo, PHQ-9, and EKGs. These tests are used to diagnose COPD and Pulmonary Fibrosis, Peripheral Vascular Disease, Major Depressive Disorder, and Congestive Heart Failure, respectively.

Coding for those conditions would collectively increase the yearly reimbursement from Medicare by over $13,000 per patient on average.

Former employees of Oak Street Health tell The Capitol Forum that the company regularly tests its patient population using the above tests, and that one abnormal reading from a test was often enough to code a condition without any further investigation. Several employees have previously singled out Oak Street Health’s use of the QuantaFlo device, produced by Semler Scientific (SMLR), to diagnose vascular disease as problematic, given the device’s capacity to produce inaccurate results.

“There were a number of people who had a terrible exam with the QuantaFlo, with results telling me that they should be having terrible blood flow, but their reported history and physical exam would show no indication of that,” a former physician said. Regardless of the questionable results, the physician said that a bad score on a QuantaFlo test would often be enough for Oak Street Health to diagnose the patient with PVD.

“We always had to look at QuantaFlo,” a former nurse coder said, “I wasn’t a big fan of that, but they said that was a definitive tool for diagnosing PVD, so we coded it. But there are a lot of aspects to that diagnosis that wouldn’t be looked at. You can have low blood flow from being on blood thinners, for example, and not have the disease, but that wouldn’t be taken into account.”

According to a former physician at Oak Street Health, “testing was essentially a fishing expedition to find potential risk adjusting codes,” and patients of Oak Street Health have complained on the company’s Facebook page about having to go into their clinics often to take what they felt were repetitive and unnecessary tests.

A Capitol Forum analysis found that, if the 2018 prevalence rates were applied to Oak Street Health’s current population of roughly 132,000 patients, Medicare could potentially be paying hundreds of millions of dollars per year over what it would pay if Oak Street Health prevalence rates were in line with national averages for Medicare beneficiaries.

Some patients coded for conditions without being tested for them. As previously mentioned, the internal documents recommend using echocardiogram tests to increase diagnosis rates for congestive heart failure.

In at least two cases, it appears that Oak Street Health physicians did not even wait for the results of echocardiograms before diagnosing patients with congestive heart failure.

A current employee at Oak Street Health told The Capitol Forum that they recently came across charts for two patients that had both been diagnosed with heart failure. However, their medical record only showed that the provider had ordered echocardiographs and chest X-Rays; there was no indication that those tests had even been performed, let alone used to confirm congestive heart failure.

Documentation shared with The Capitol Forum by the employee does not indicate any congestive heart failure.

“These were previously documented conditions that needed to be reconfirmed as active for 2022,” the employee said, “Oak Street has been getting paid for these diagnoses when there was no medical finding.”

“I had a similar thing the other day as well,” the employee continued, “patient was coded for heart failure. I looked for an echocardiogram and there was no echocardiogram. The thing is, the chart showed that they had a totally normal EKG last year. Their heart is fine, but we’re coding them like they have congestive heart failure.”

A former physician who worked at another Oak Street Health clinic in a different state said that their manager verbally told them that “we need to be capturing more heart failures,” a request that the physician resisted.

“I am not going to order an echocardiogram for every other patient that we have in order to satisfy heart failure coding requirements,” the former physician said.

Training documents. The risk adjustment plan also requires providers to “attend quarterly Capstone Risk Adjustment sessions.”

Oak Street Health uses an outside consultancy called Capstone Performance Systems to train doctors, nurses, medical assistants, and clinic informatics specialists in how to code conditions in order to increase reimbursement. Staff are required to attend these training sessions quarterly.

Capstone Performance Systems did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

A former employee at an Oak Street Health clinic provided The Capitol Forum with a slide deck from a Capstone training session in 2020.

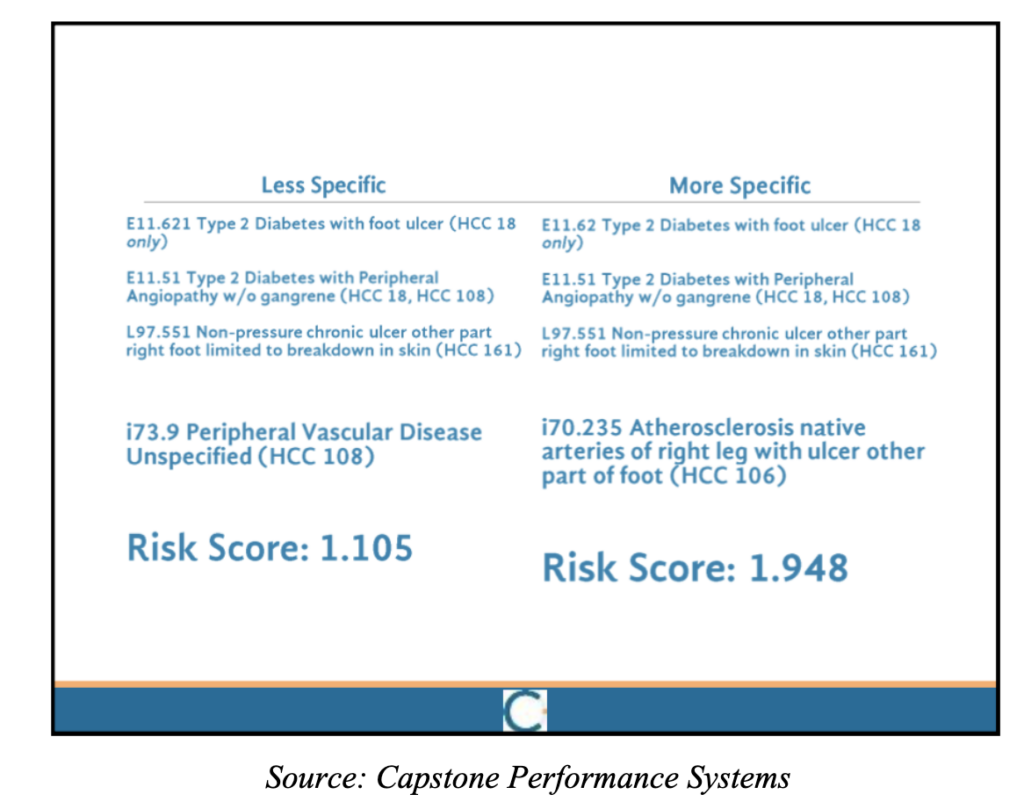

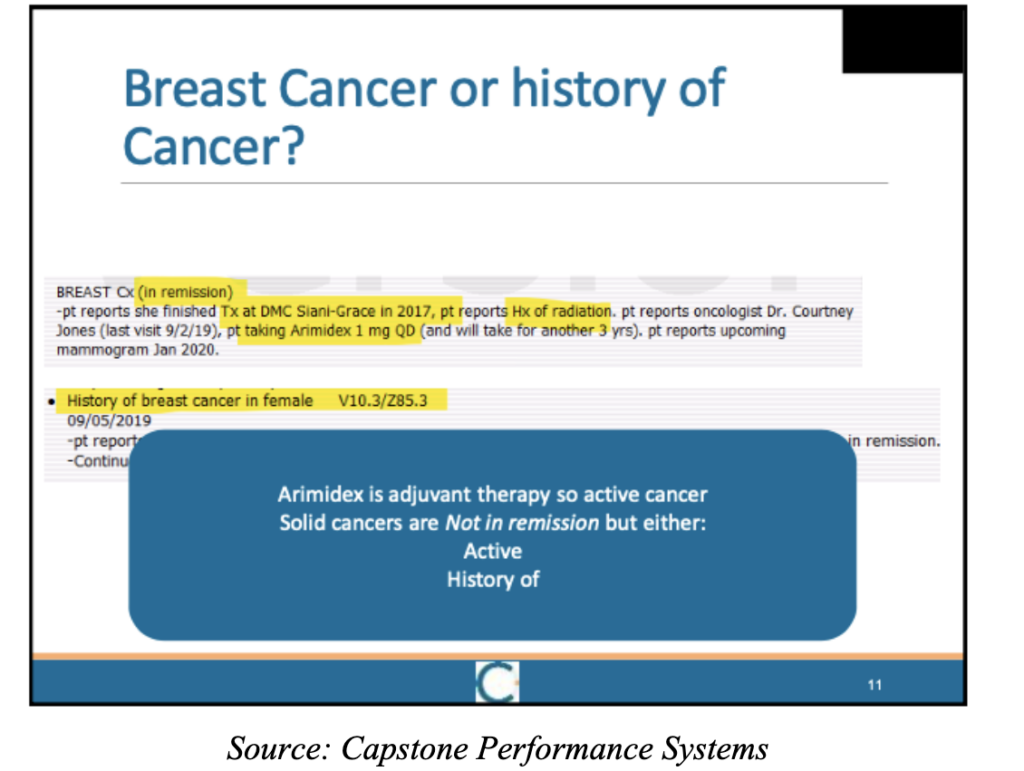

Key to increasing a patient’s risk score is diagnosing them with diseases that are linked to HCC (hierarchical condition category) codes. Slides from the presentation make it clear that coding certain diseases in certain ways can map to different HCC codes and dramatically increase a patient’s risk score.

For example, the following slide shows that classifying unspecified peripheral vascular disease as “Atherosclerosis native arteries of right leg with ulcer other part of foot” could increase a patient’s risk score by almost a full point.

Other slides in the presentation detail several methods that Oak Street Health doctors can use to diagnose conditions that will increase a patient’s risk score.

Other slides in the presentation detail several methods that Oak Street Health doctors can use to diagnose conditions that will increase a patient’s risk score.

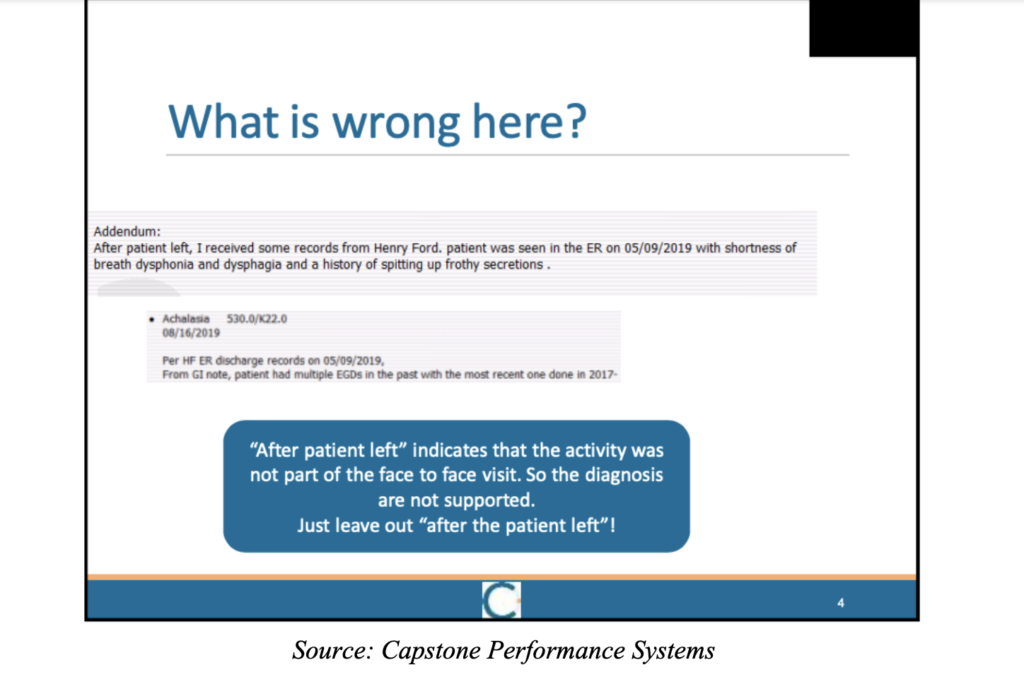

One method the presentation advises is editing medical records so that conditions not observed by a doctor could still be diagnosed. The chart uses an example of a doctor who noted that symptoms for a disease were not viewed in person by the doctor but instead found in a medical record after the patient left.

According to the presentation, that “indicates that the activity was not part of the face to face visit. So the diagnosis are not supported.”

“Just leave out ‘after the patient left’!” the slide advises.

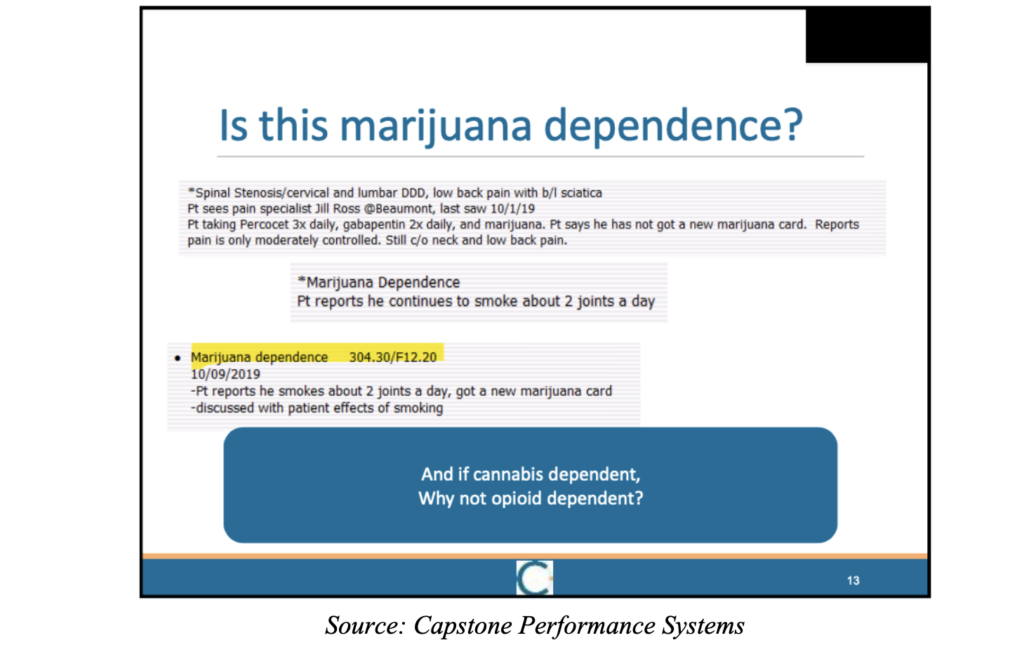

Other slides ask the audience open-ended questions about whether a provider can diagnose certain conditions based off of scant information provided to them. According to the employee who attended these training seminars, the answer was almost always yes.

In the employee’s clinical opinion, however, many of the examples Capstone used to support diagnoses, such as diagnosing opioid dependence in a patient that took three Percocet a day, were far-fetched. Those diagnoses, the former employee said, should require more investigation, such as seeing if the patient was going through withdrawals or if their tolerance had increased.

A former physician who attended similar trainings explained that, while the text on slides left the answers open to interpretation, “the meat of the presentation and the conversations around the presentation would lean towards always diagnosing a condition.”

“As I went on,” the former physician continued, “it stopped being about learning, and more about ‘How do I turn this into an HCC?’ The goals of my day-to-day were about making sure all the HCCs were captured… there are a lot of good providers and really smart people at Oak Street doing it for all the right reasons, but the business side of it, the people saying that we need to capture as many HCC codes as possible, is screwing it up.”

Another slide recommends diagnosing a patient’s remissive breast cancer as active because of the preventative medication they were taking.

Former medical providers at Oak Street Health have raised concerns over diagnostic methods like this, stating that preventative medications taken for one condition could be used to diagnose an irrelevant condition that shared a medication or treatment. According to a former physician, a motto at the company was that “treatment is prima facie evidence of a diagnosis,” and a slide from another Capstone training told physicians to “Remember Mantra #3- if you are treating, you diagnosed.”

However, in diagnosing active breast cancer in a patient that is in remission, Dr. Gilfillan said that, in his opinion, this practice took a cavalier attitude towards the effect that hunting for risk adjusting conditions could have on patients.

“Electronic health records belong to patients,” Dr. Gilfillan said, “they read them. No empathetic clinician would tell a woman who is taking medicine to prevent a recurrence, or a second cancer, that she has ‘active breast cancer.’ It would be devastating. I am sure no risk score coding or Medicare Advantage firm CEO would want to hear that about themselves or a loved one. This is a perfect example of how the risk score coding game can override clinical judgement and lead to real patient harm, and of the single-minded obliviousness of code hunters.”

“The good news is that the vast majority of clinicians would never do it,” he added.